Weird little factoid about me: my minor in undergrad was Russian History (amazing blog on the subject.) I assure you that it was not because of some deep abiding interest in Russian History- although it did become a deep, abiding interest. It was because I am terrible at life's paperwork and always registered for classes late. That meant I ended up taking Russian Masterpieces of the 19th Century and Russian History post-1917, Russian History pre-1917, Russian During the Revolution, Communism and Stalin, etc.

In my final semester, my advisor was all like, "Hey Terrible-Student-Whose-Name-I-Can-Never-Remember, take another Russian literature class and you'll have an official minor." So that's what I did and now I can act like a smarty-pants Jeopardy contestant because I know all of this obscure Russian history.

J/k. I don't remember shit.

Since the weather in Pittsburgh has been miserably arctic, I thought I'd write about places even more arctic and forbidding, like the former USSR, modern-day Russia, and the coldest of the cold, Siberia. (As I write this the temperature in Yakutsk is -38 degrees Celcius. This is considered "fair" weather.) Zdorovo!

NON-FICTION

White fever: A Journey to the Frozen Heart of Siberia by Jacek Hugo-Bader

Hugo-Bader is a Polish journalist (White Fever is a translation) and according to his biography also a "weigher of pigs and counsellor of troubled couples." In 2007, as a birthday gift to himself, Hugo-Bader decided to drive from Moscow to Vladivostok, a distance of 9037 km (over 5600 miles.) That's a weird ass birthday gift, if you ask me. If you are looking for a straight-up travelogue then you should skip this title. Hugo-Bader does write about his actual travelling (more in the beginning and end), but most of this story is about the people he meets on the road. It's the dark side of Siberia explored, the side where alcoholism is rampant, the AIDS epidemic is exploding, suicides and murders are endemic- a Siberia "killing itself." There are wonderful moments of dark humor, with hopeful rappers, reindeer shepherds, and shamans, but ultimately Hugo-Bader is a journalist- and if it bleeds, it leads.

Cycling Home from Siberia : 30,000 Miles, 3 Years, 1 Bicycle by Rob Lilwall

In September, a group of friends and I are riding our bikes from Pittsburgh to Washington, DC via a very nice rails-to-trails system. We are riding to DC, a distance of about 325 miles and taking a train back. I'm a little afraid: What if I can't do it? Then there's this guy. Rob Lilwall. Rides his bike from Siberia to freaking England, via Papua New Guinea, Australia, China, and Afghanistan. (For all of you smart asses, I am aware that you can't cycle to Australia; he took a damn boat.) It isn't a typical cycling travelogue: he doesn't get into the mechanical problems (there's NO way he didn't have them) or what he ate (protein, bro!) He does recommend eating ice cream, as it's full of calories and fat. Fine by me. Cycling Home is more introspective, he wonders why he's doing this trip and frankly, a little "Jesus-y" at times. (Lilwall is a born-again Christian.)

On the Run in Siberia by Rane Willerslev

Hugo-Bader is a Polish journalist (White Fever is a translation) and according to his biography also a "weigher of pigs and counsellor of troubled couples." In 2007, as a birthday gift to himself, Hugo-Bader decided to drive from Moscow to Vladivostok, a distance of 9037 km (over 5600 miles.) That's a weird ass birthday gift, if you ask me. If you are looking for a straight-up travelogue then you should skip this title. Hugo-Bader does write about his actual travelling (more in the beginning and end), but most of this story is about the people he meets on the road. It's the dark side of Siberia explored, the side where alcoholism is rampant, the AIDS epidemic is exploding, suicides and murders are endemic- a Siberia "killing itself." There are wonderful moments of dark humor, with hopeful rappers, reindeer shepherds, and shamans, but ultimately Hugo-Bader is a journalist- and if it bleeds, it leads.

Using a place as punishment may or may not be fair to the people who are punished there, but it always demeans and does a disservice to the place.When I started Travels I was expecting a brief history of the Soviet Union, maybe a little about the fall of Communism and it's affect on the population and of course, the role of Siberia in all of that. What I didn't expect was an epic, sweeping historical, cultural, and psychological story about Russia (in all her various forms) told with warmth and humor. Frazier writes about Siberia's more famous exiles (Dostoevsky, Lenin, Stalin) and some not-so-famous, like Natalie Lopukhin (exiled for copying the Empress' dress, no kidding.) He also chronicles life in the post-Soviet landscape, with less despair and more hope than many other authors. Frazier has an obvious love for Russia and it shows in his tender depictions of her.

Cycling Home from Siberia : 30,000 Miles, 3 Years, 1 Bicycle by Rob Lilwall

In September, a group of friends and I are riding our bikes from Pittsburgh to Washington, DC via a very nice rails-to-trails system. We are riding to DC, a distance of about 325 miles and taking a train back. I'm a little afraid: What if I can't do it? Then there's this guy. Rob Lilwall. Rides his bike from Siberia to freaking England, via Papua New Guinea, Australia, China, and Afghanistan. (For all of you smart asses, I am aware that you can't cycle to Australia; he took a damn boat.) It isn't a typical cycling travelogue: he doesn't get into the mechanical problems (there's NO way he didn't have them) or what he ate (protein, bro!) He does recommend eating ice cream, as it's full of calories and fat. Fine by me. Cycling Home is more introspective, he wonders why he's doing this trip and frankly, a little "Jesus-y" at times. (Lilwall is a born-again Christian.)

Lost and Found in Russia : Lives in a Post-Soviet Landscape by Susan Richards

Of all the books on this list, this is the one I found the most depressing. Considering what we're dealing with here, that is saying something. Perhaps because I did read a lot about the fall of Communism in Russia (and you know, lived through it) I didn't find the despair (and poisoned food and murder and suicide) all that surprising- and Richards, a long-time traveler (1992-2008) in post-Soviet Russia didn't either. One reviewer said, "Russia is darker and crazier than I though." Richards documents the crazy and harsh transition with a clear love of Russia: the language, the culture, and the people. A lot of the writing feels informal because Richards is talking about her real friends, not "subjects." What makes this story all the more tragic is that it's now; this isn't "history" it's current affairs.

Of all the books on this list, this is the one I found the most depressing. Considering what we're dealing with here, that is saying something. Perhaps because I did read a lot about the fall of Communism in Russia (and you know, lived through it) I didn't find the despair (and poisoned food and murder and suicide) all that surprising- and Richards, a long-time traveler (1992-2008) in post-Soviet Russia didn't either. One reviewer said, "Russia is darker and crazier than I though." Richards documents the crazy and harsh transition with a clear love of Russia: the language, the culture, and the people. A lot of the writing feels informal because Richards is talking about her real friends, not "subjects." What makes this story all the more tragic is that it's now; this isn't "history" it's current affairs.

On the Run in Siberia by Rane Willerslev

Every once in a while I'll see a television show that makes me want to be an adventurer. Then I read a book like this and realize I'm perfectly content managing a library, riding my bike, hanging out with my husband and feeding my cats. Idealist Rane Willerslev is a Danish anthropologist who heads into the Siberia wild with an idea of forming a fair-trade fur cooperative with the Yukaghir hunters. Since the fall of Communism, the fur trade had been monopolized by a very corrupt regional corporation- who apparently stop at nothing, including murder, to hang on to that monopoly. Willerslev, instead of creating his cooperative, is actually forced into hiding in the Siberian wilds: which is where the real story starts. Willerslev faces frostbite, starvation, exile, and political corruption during his year with the Yukaghir hunters. On the Run is shocking and at times deeply (surprisingly) moving. It also makes me grateful for my hot coffee and warm house.

FICTION

Dog Boy by Eva Hornung

Dog Boy by Eva Hornung

In 1998, the end of the Cold War and the breakdown of the Russian economy created over 2 million homeless children. Many parents simply packed up and left, leaving children as young as two years old to fend for themselves. Dog Boy was inspired by the true story of Ivan Mishukuv, a four-year old who lived with a pack of wild dogs for two years until he was "rescued." If you are interested in the real story, it is included in Savage Girls and Wild Boys: A History of Feral Children by Michael Newton. Dog Boy is a work of fiction (and one of my favorite books), but it is so beautifully and realistically rendered that I found it so easy to imagine to sleeping in a pile of smelly wild dogs, burying my face in their warm bellies to escape the harsh Moscow cold and sharing scraps of food with them. Four year old Romochka and the dogs work together to survive and that includes preying on other people. Eventually they earn the notice of the "authorities" and Romochka is "rescued" from the dogs. I honestly don't know what I expected, but I found the ending heart-breaking. This book stayed with me for a long time.

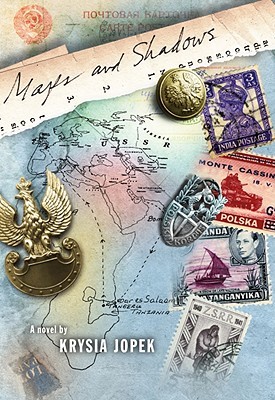

Maps and Shadows by Krysia Jopek

Hey, did you know that during World War II almost 1.5 million Polish civilians were deported to forced labor camps in Siberia? Isn't that a cheerful little fact? As should be apparent by now I read a lot of depressing books. This is a very short (151 pages) book that packs a sharp punch. The writing is so beautiful and lyrical; the story so horrifying and bleak. Taken from Jopek's real family history, the story is told from the point of view of five different members of her family who were deported from Poland after the Soviet invasion. "Deported" is a nice word for what actually occurred: the loss of their entire lives. The family is separated multiple times, members being sent to Africa, England, Uzbekistan, Italy- all eventually ending up in the United States. The book has a lot of unusual touches, but the poetry interspersed throughout the book was my favorite.

The People's Act of Love by James Meek

I am not finished with this book yet. I found it while looking up other books about Siberia. It's fascinating. I love the main character, Samarin and I'm dreading what awful shit is about to happen to him. So far he's charming, handsome, bright, and referred by local townspeople as schastlivchik (the lucky one.) Anyone who has ever read a book knows that doesn't bode well for him. Honestly, who wants to read nearly 400 pages about someone's awesomeluckygreat life? From the book jacket, I gather Samarin gets tossed in a Siberian prison camp, escapes and ends up in a bizarre, totally lawless town full of interesting characters. James Meek's writing has been compared to Tolstoy's for it's humane voice and his current book, The Heart Broke In, was shortlisted for the 2012 Costa Prize.

Snowdrops by A.D.Miller

FICTION

Dog Boy by Eva Hornung

Dog Boy by Eva HornungIn 1998, the end of the Cold War and the breakdown of the Russian economy created over 2 million homeless children. Many parents simply packed up and left, leaving children as young as two years old to fend for themselves. Dog Boy was inspired by the true story of Ivan Mishukuv, a four-year old who lived with a pack of wild dogs for two years until he was "rescued." If you are interested in the real story, it is included in Savage Girls and Wild Boys: A History of Feral Children by Michael Newton. Dog Boy is a work of fiction (and one of my favorite books), but it is so beautifully and realistically rendered that I found it so easy to imagine to sleeping in a pile of smelly wild dogs, burying my face in their warm bellies to escape the harsh Moscow cold and sharing scraps of food with them. Four year old Romochka and the dogs work together to survive and that includes preying on other people. Eventually they earn the notice of the "authorities" and Romochka is "rescued" from the dogs. I honestly don't know what I expected, but I found the ending heart-breaking. This book stayed with me for a long time.

Maps and Shadows by Krysia Jopek

Hey, did you know that during World War II almost 1.5 million Polish civilians were deported to forced labor camps in Siberia? Isn't that a cheerful little fact? As should be apparent by now I read a lot of depressing books. This is a very short (151 pages) book that packs a sharp punch. The writing is so beautiful and lyrical; the story so horrifying and bleak. Taken from Jopek's real family history, the story is told from the point of view of five different members of her family who were deported from Poland after the Soviet invasion. "Deported" is a nice word for what actually occurred: the loss of their entire lives. The family is separated multiple times, members being sent to Africa, England, Uzbekistan, Italy- all eventually ending up in the United States. The book has a lot of unusual touches, but the poetry interspersed throughout the book was my favorite.

Ice Garden

This scrim of the inner room

The door of some other now, the book

Of will unknown. The book of how

And why drowned, encrusted under:

Sisyphus longed for a beginning, middle

And end to make it all bearable or seem

To have context. The shortest distance

Between two points can be viole[n]t

Those wounds in the armpits

Wary at the lookout, ready to bow

And disregard history's narrative.

The People's Act of Love by James Meek

I am not finished with this book yet. I found it while looking up other books about Siberia. It's fascinating. I love the main character, Samarin and I'm dreading what awful shit is about to happen to him. So far he's charming, handsome, bright, and referred by local townspeople as schastlivchik (the lucky one.) Anyone who has ever read a book knows that doesn't bode well for him. Honestly, who wants to read nearly 400 pages about someone's awesomeluckygreat life? From the book jacket, I gather Samarin gets tossed in a Siberian prison camp, escapes and ends up in a bizarre, totally lawless town full of interesting characters. James Meek's writing has been compared to Tolstoy's for it's humane voice and his current book, The Heart Broke In, was shortlisted for the 2012 Costa Prize.

Snowdrops by A.D.Miller

I smelled it before I saw it.In Russia, a "snowdrop" is a corpse that lies hidden in the snow until the spring thaw. You are welcome for that pleasant imagery. This is a weird little book about the hedonistic life of Nick Platt, an English lawyer in Moscow for on business. I'm not even entirely sure I enjoyed this book (It was long-listed for the Man Booker. I generally dislike Man Booker choices. Because I'm a peasant.) Nick Platt isn't particularly a likable character: he's sexist, easily led, a bit amoral. He doesn't actively act unethically, but he doesn't ask too many questions either: of his employer and their shady oil deal he's brokering or of the sisters he "rescues" from a purse snatching, Masha and Katya. Instead, he is swept away by the exotic and intense lifestyle of Moscow's young club scene. Written as a letter to his fiance, there is a lot of justifying, not a ton of taking responsibility. Platt is surprised that he was taken in by Masha and Katya, when most of his instincts about both women are dead wrong. Moscow is so vividly written and described that it is a character in itself. It's magical and debauched, corrupt and kind, a place for the young.

TO READ

This is technically a Young Adult title. It has been recommended for readers who love The Book Thief by Markus Zusak (which better be ALL the readers who read The Book Thief.) It's the story of an artistic Lithuanian girl and her family taken in the middle of the night, put on a train, and sent to Siberia. That would be a great way to spend your teenage years, no? This book was kind of over-hyped when it was released, but enough people have recommended it that I'm game.

Tseluyu!

No comments:

Post a Comment